Chad Beguelin knows how to make you fall in love with a character. Whether it’s redeeming The Prom’s self-absorbed Broadway diva Dee Dee Allen or preserving the innocent magic of beloved heroes like Aladdin and Buddy the oversized Christmas elf, you can count on his Broadway librettos and lyrics to warm your insides. Every so often there’s also a sharp-elbowed zinger to keep you on your toes.

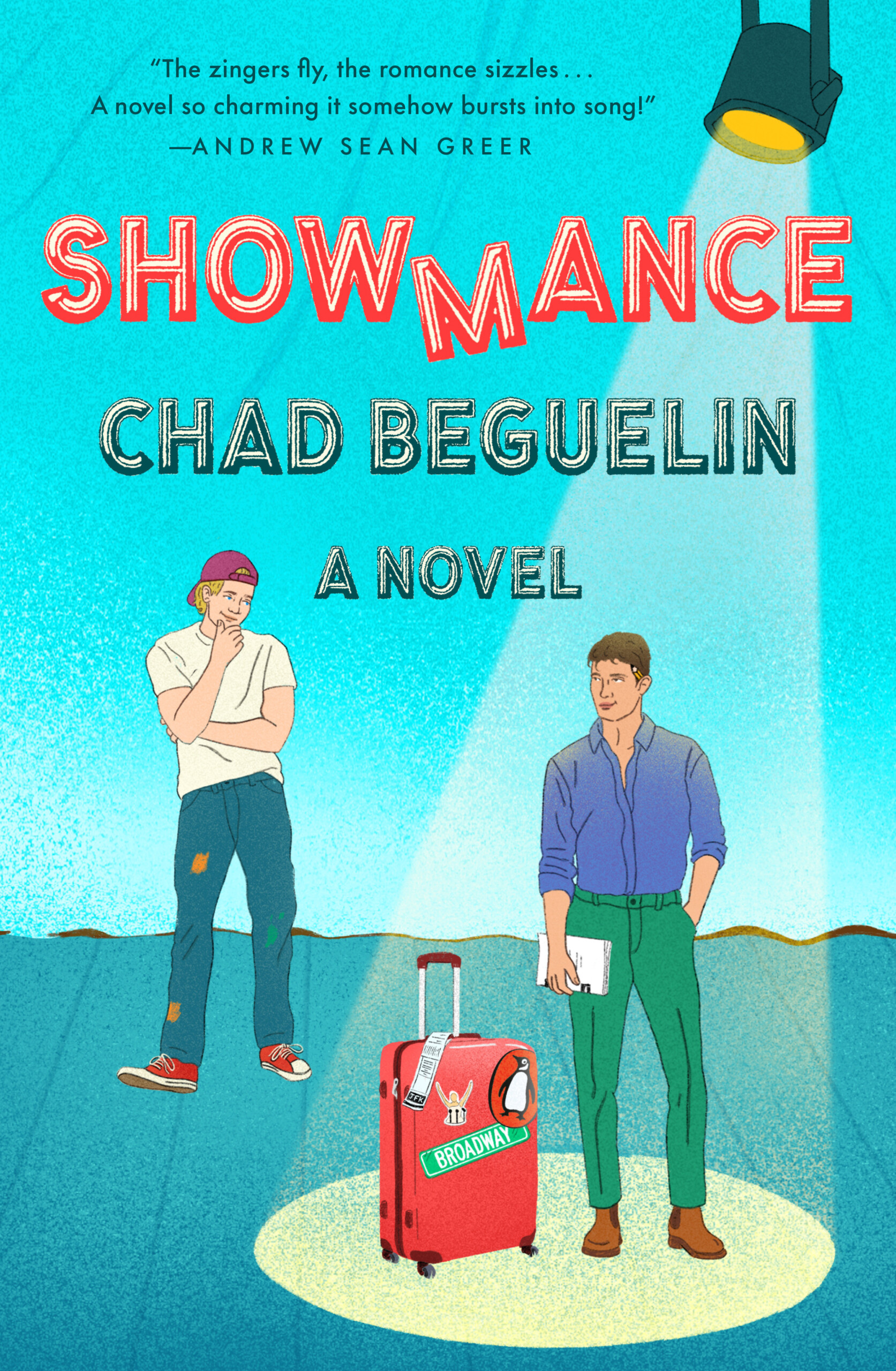

Beguelin brought all these finely honed skills to his debut novel, a queer rom-com aptly titled Showmance. It’s a brand-new medium for this creature of the stage, but the story takes place in his own backyard. His main character, Noah, fresh off a Broadway flop, hides out in his hometown in rural Illinois where a community theater fixes up his career-ending musical—and, of course, the titular showmance ensues.

In a Q&A with Broadway.com Editor-in-Chief Paul Wontorek at the Drama Book Shop, Beguelin talked about his own background growing up in Illinois and becoming the artist he is today because of the community theater that captured his heart. Read excerpts from the conversation below.

Tell me when you started on this book.

Well, I started before we started working on The Prom. I did a few chapters and I thought, “Oh, this is a marathon. I don’t know if I can do this.” So I put it away and went to work on The Prom. And then in The Prom we had an opening number that was totally confusing and not working at all, and I said, “Well, there’s this book I’ll probably never finish and this is what happens: They close on opening night.” So we were all like, “Yeah, let’s do that!” And so we used that idea. Then I started working on the book again and I thought, “Oh, can I do another piece that starts that way?” I was like, “Well, I’ll just steal from myself.”

Let’s give the basic setup here: So the show opens, it tanks and Noah is on a plane. Where’s he going?

Well, a family emergency calls him home, and while he’s there, he gets talked into directing his flop musical at his Podunk small-town community theater. He writes everybody off as hicks and does it begrudgingly. And then they slowly start making these really smart suggestions and the show suddenly gets better and better and better. He’s completely thrown for a loop, and at first he’s like, “Am I going to actually take their notes?” But then he realizes, “Oh my God, these are better notes than I ever got from these professional Broadway people.”

(Photo: Deen van Meer)

How much of you is in Noah?

A lot of me. I hope I’m not as much of a dick as he is at the beginning because he’s pretty harsh. But I’m from a small town and I grew up in the community theater there. When I was 15, I was like, “I want to write direct shows here.” And miraculously they were like, “Cool. Okay, do it.” I didn’t have a driver’s license and I was directing shows and writing shows—so that all is true.

I want to hear about you as a kid and you finding that community theater. Tell me about all that.

Well, like Noah, I saw a production of Oliver! at my community theater and I didn’t want to leave. I thought they would maybe do it again if I stayed. And my mom was like, “No, it’s over, but you can be involved.” And so I just started doing every single show I could with them. Then when I was 15, like Noah, I wrote a really horrible musical version of Pinocchio. Those terrible lyrics were my terrible lyrics. But they put it up and they let me direct it. After that, I did your standards like Dames at Sea and Pippin and all that kind of thing.

What was your first time on stage there?

I was a young Jewish boy in Fiddler On The Roof. I always ruined the choreography, but they thought it was cute because I was really little.

You are a very established Broadway name and have a lot of shows under your belt. Is it fun to be a newbie at something?

There were so many things I didn’t know. I learned that I’m a “pantser,” which means writing by the seat of your pants. And I think that’s mainly because in musicals, we always start with an outline and song spotting so that the songwriters can go off and the book writers can go off, and then we come back and we’re all on the same page. I was like, “I don’t want to do that with this. I want to just see where it takes me.” So it was very freeing to just be like, “I don’t know what’s going to happen.” I had a general thrust, but the nuts and bolts just came as I went along.

Who’s your dream reader to find this book? This is in a genre of books that’s very popular now, but we didn’t grow up with queer rom-coms.

You’re right, this was not around when we were younger. Nothing positive was. When we were younger, most stories that were queer were very sad and had terrible endings. Around when Heartstopper came out, I was really jealous that we didn’t have this. That’s one of the reasons I was excited to write it. I thought, “Wow, we can tell happy stories now and we can tell romantic stories that don’t have to end in suicide or some horrible death.”

What are your goals moving forward as a writer and an artist? How do you keep things interesting for yourself?

I think the best advice I ever got was, “It’s got to be bad before it can be good.” I was working with Jerry Mitchell on a benefit once and Cyndi Lauper came in. They were talking about a musical that had just opened and it flopped and it was just terrible. She wondered what happened and Jerry’s like, “Well, I just don’t think the score was that good.” And she said, “Why didn’t they just write it better?” So I will sometimes do that when I’m frustrated. I’ll be like, “Okay, Chad—just write it better.” Good advice from Cyndi.